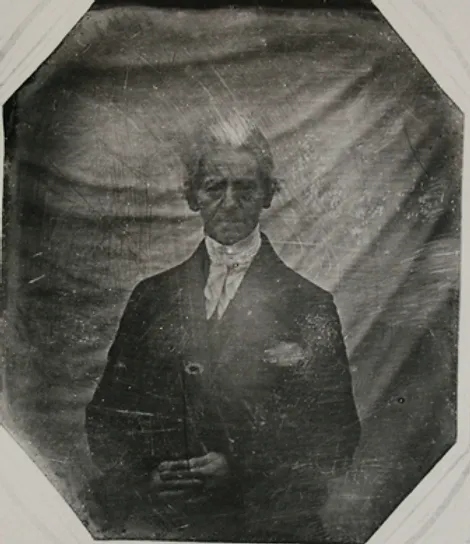

Robert Motherby, long-time friend of Immanuel Kant, was born on December 23, 1736 in Hull (Yorkshire, England). He had four brothers and three sisters. His father George (born on December 20, 1688), married to Anne Hotham, died in 1748 while Robert was still a child. Robert Motherby probably came to Königsberg around 1751: The English merchant Joseph Green (1727-1786), who ran a business in Königsberg at the time, was searching for a reliable young Englishman to be his assistant and one day become his partner. Joseph Green, a Hull native like Robert Motherby, was unmarried and had no children. While searching for a particularly responsible young man, Green had spoken with a business associate based in Hull, who recommended Robert Motherby to him. Robert Motherby, who arrived in Königsberg with no knowledge of German, soon proved himself and became Green’s partner. At Green’s request, he finally took over the company completely and continued to lead it successfully.

As a young lecturer, Kant had very little income. Nevertheless, he frequently invested small sums with Green & Motherby, who managed his assets so well that he later became quite wealthy. Kant, Green, and Motherby were not only business partners, but also close friends. A champagne glass, handed down from Robert Motherby to his son William, provides evidence of this friendship with a revealing engraving:

This engraving proves that Kant and Robert Motherby were already friends in 1763. Their friendship, which lasted until the end of Robert Motherby’s life (1801) therefore extends much further back than assumed by most Kant biographers.

Robert Motherby and Charlotte Toussaint (April 30, 1742- September 10, 1794) were married in 1767. Charlotte was one of several daughters of Jean Claude Toussaint, (born May 21, 1709 in Magdeburg, died December 23, 1774 in Königsberg) and his wife Catherine, nee Fraissinet (born 1719 in Königsberg and died October 21, 1744 in Königsberg). Jean Claude Toussaint was a co-proprietor of the trading company Toussaint & Laval. His parents came from France.

Robert and Charlotte Motherby had 11 children (6 sons and 5 daughters; one son and one daughter died shortly after birth). Many periods of confinement for childbirth had severe effects on Charlotte’s health; she died in 1794 at the age of only 52.

Kant was a regular guest in the Motherby home even in his later years. Kant’s student and later colleague, Karl Ludwig Pörschke (1752-1812), wrote to the philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte on February 7, 1798: “Because Kant is no longer giving lectures and has withdrawn from all society except for the house of his friend Motherby, he will gradually become unknown here as well, and even his reputation will decline.”

Sunday lunch in the Motherby home was a fixture in Kant’s later life. He watched the Motherby children grow up and was practically part of the family. Robert Motherby always invited him in writing; on Sunday mornings, he sent a servant to Kant with an invitation. When Kant for his part invited Robert Motherby to lunch, he sent his servant Lampe to him with an invitation on the morning of the same day. Kant felt that this polite gesture was very important because he always wanted the person being invited to have the opportunity to decline. Even in such mundane matters, consideration and respect for the freedom of others were always very important to Kant.

In 1892 (i.e., long after Kant’s death), the Königsberg banker and patron of the arts Walter Simon commissioned the historical painter Emil Doerstling to produce a painting of Kant hosting guests in his house. According to a publication by Christian Friedrich Reusch, “Kant and his Dining Companions” from 1847, Doerstling depicted well-known public figures from Königsberg who were frequently guests of Kant (including Robert Motherby, sitting to Kant’s left in the painting).

A copy of this painting hangs in the museum of the restored Königsberg cathedral in Kaliningrad.

The children of Robert and Charlotte Motherby enjoyed a free-spirited upbringing in which Kant played a significant role, and spoke German, English, and French fluently. Kant saw to it that from the age of 6 to 13, George and later also William and Joseph were sent to the Philantropinum, a school in Dessau highly esteemed by Kant for its progressive teaching methods. Kant’s letters to Christian Heinrich Wolke on March 28, 1776 and to Johann Bernhard Basedow on June 19, 1776 concerning the acceptance of George Motherby (born August 7, 1770) to the Philantropinum have been preserved.

Another letter from Kant, which is quite different in nature but nonetheless has a pedagogical goal, is his missive of February 11, 1793 to 20-year-old Elisabeth Motherby (April 27, 1772 – August 29, 1807), a daughter of Robert and Charlotte Motherby. Kant sent Elisabeth some letters addressed to him by a “young enthusiast”, who was having thoughts of suicide due to romantic difficulties, and included with them a letter of his own in which he tells Elisabeth that given the “good fortune of her upbringing”, he saw no need to “warn against such wanderings of a sublimated imagination.” Nevertheless, he felt that reading the enclosed letters could serve to make her “perception of this good fortune even more vivid.” The fact that Kant felt called upon to give such counsel shows how deeply he felt his role as a paternal friend.

Robert Motherby died on February 13, 1801, almost exactly three years before Kant’s death. For Kant, the death of his friend of many years was a painful loss.

Robert’s sons George (1770 – 1799) and Joseph (1775 – 1820) followed their father’s footsteps and likewise became merchants; they both died young. Joseph left behind his wife Marie Thérèse and two sons, who apparently later went to St. Petersburg and were then lost to history.

William Motherby (1776 – 1847) studied medicine in Königsberg and Jena. To give him a good start in Jena, Kant wrote to the physician Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland (Professor emeritus at the University of Jena) on April 19, 1797:

“My dear Sir, I hope that you will have received my letter from Mr. D. Friedländer in Berlin, thanking you for your gift of the book concerning the lengthening of life.

— I would now like to request your goodwill and friendship for Mr. Motherby, whom I have the honor of presenting to you. He is a young man of English descent, born in Königsberg, very talented and with many acquired skills, of firm resolution and virtuous thinking, open-minded and humane like his father, who is an English merchant residing here, respected and loved by everyone and my trusted friend for many years. — He has thoroughly studied all that was to be learned from me and at our university in his field of study (medicine), and I therefore request that the more numerous and greater resources for his study in your locale be made available to him, whereby he will not be inconvenienced by the expenses required for this purpose.”

Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland wrote to Kant on September 30, 1797:

“My dear Sir, I cannot describe how happy I was to receive the two letters which you honored me by sending, and I would not have been able to restrain these feelings for so long unless it was so that I could also write you at the same time with some news about young Motherby, whom you had recommended to me.

— I am therefore even happier to be able to give you the best report concerning him. I have not often seen a young man who combines such a liveliness of spirit with a character of such resolution, honesty, and morality, and who has become so dear to me in such a short time. His deportment is impeccable, his industriousness is indefatigable, and he belongs to those of my listeners who are a true encouragement and instruction in my business. I have nothing to criticize about him except that he visits me too rarely, and to ensure that he comes to see more often, I will bring him into my conservatory and collegium disputatorium this winter. I promise you that I will do everything in my power to develop him into a useful and productive citizen.”

William Motherby received his medical degree in Edinburgh in 1798 and dedicated his dissertation to his father’s friend and academic teacher Immanuel Kant, who wrote in this regard to the physician and philosopher Johann Benjamin Erhard on December 20, 1799:

“One thing that I am very happy about, however, is that HE William Motherby, who is currently studying medicine in Berlin, is likewise there; I request that you converse with him; like his worthy father, he is my excellent friend, a cheerful, goodly young man. He dedicated his inaugural disputation in Edinburgh last year (de Epilepsia) to me, and I ask that you please thank him for this on my behalf. — Integrity is an intrinsic part of his character and that of his family, and your acquaintance will be entertaining and useful for both you and him.”

Dr. med. William Motherby introduced cowpox vaccination in Königsberg and became a respected physician, although not suitable for everyone, as attested by his friend Ernst August Hagen. Prof. Ernst August Hagen (1797 – 1880), Professor for Art and Literary History at the Albertina and son of the Königsberg court pharmacist and founder of scientific pharmacy, Karl Gottfried Hagen (1749 –1829), wrote in his memorial speech for William Motherby:

“Although his impetuous nature and habit of interrupting his patients before they had finished describing their complaints did not endear him to everyone, nevertheless, those who did seek out his advice and assistance were completely satisfied with him and trusted his skill to their last breath. Not only the patient, but the entire household always treated his appearance as a celebration, and his faithful participation in all events, his consistently good humor, and the confidence and presence of mind with which he encountered the acknowledged misfortune ensures him a grateful memory in the minds of many. ….. Kant set much store by his extensive knowledge and gave him a gratifying testimonial in a letter to Soemmerling. ..……..

No matter how often he proved to possess far more knowledge than his dining companions and constantly outshone them with his adept arguments, he certainly never did anyone harm, and anyone who did not learn from his explanations was at least never unpleasantly affected by his contradiction.”

Christian Friedrich Reusch, the younger son of Kant’s dining companion and professor of physics Karl Daniel Reusch, mentions in 1847 in “Kant and his Dining Companions” that “Dr. med. William Motherby” was a guest at Kant’s table once or twice per week. He also writes: “William was extremely talented and beloved, with a sparkling and apt wit. He appeared to have inherited his love of etymology from Kant. His liveliness and quick grasp of all subjects made him popular in every social gathering, and he was often at the center of conversation.” A respected government official from another city who heard Motherby speak in such a spirited matter at a gathering expressed his enormous pleasure at hearing it, since nothing of the like could be found in his city. Motherby attempted to promote the introduction of cowpox vaccination through small pamphlets. His talent was such that had he wished to, he could have a popular writer with his lively brief descriptions… It was Dr. med. William Motherby’s lovely idea to have the friends of Kant meet annually for a simple lunch on his birthday, April 22.”

William was a great admirer of Shakespeare, and at an advanced age he translated “The Merry wives of Windsor.”

William’s circle of friends included many well-known people of the day. In addition to Kant, he was friends with Wilhelm v. Humboldt, Baron v. Stein, the author Ernst Moritz Arndt, and the astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel, to name only a few.

In his book “My Travels and Saunterings with Baron Heinrich Karl Friedrich vom Stein,” Ernst Moritz Arndt, a childhood friend of William, writes about his stay at the Motherby home in early 1813:

“At my friend Motherby’s house, I experienced similar, but much more youthful and lively evenings than at Dohna’s and Schrötter’s. This was a noble, free town home, steeped in the English and Kantian spirit.” Motherby’s father was an Englishman, a native of Hull, a merchant in Königsberg, …., a friend and dining companion of Kant. The Hull-born Motherby’s sons inherited some of the spirit of that life.”

William married Johanna Tillheim (April 29, 1783 – August 22, 1842) in 1806.

William and Johanna had two children: Anna (April 15, 1807 – January 5, 1870), known as Nancy, and Robert (April 4,1808 – April 17, 1861), like his father became a physician and an agriculturist.

Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein

As the daughter of a Königsberg tradesman, William’s wife Joanna Motherby (nee Tillheim) came from a rather modest background. According to her biographer Heinrich Meisner in 1893, she had a “lively and cheerful way about her” and a “pleasing manner in speech and movement.” Meisner further writes that: “In the first years of their marriage, William was extremely busy with his practice and his work for the city, which was probably why the couple grew apart. In April 1809, Humboldt came to Königsberg as a member of the Privy Council and head of the Department for Culture and Education. He quickly became a welcome guest in the home of William Motherby, with whom he shared a reverence for Kant’s philosophy and Pestalozzi’ s pedagogy. The friendship with William Motherby was soon joined by a deep affection for Johanna. Following his departure from Königsberg, there was a lively and passionate exchange of letters between the two, which was broken off only in 1813, when Ernst Moritz Arndt entered Johanna’s life.” Ernst Moritz Arndt, who as already mentioned was a childhood friend of William, came to Königsberg in 1813 with Baron vom Stein. A close relationship developed between Ernst Moritz Arndt and Johanna Motherby, which is similarly documented through intensive correspondence (“Letters to Johanna Motherby,” published in 1893 by Heinrich Meisner in Brockhaus-Verlag Leipzig). This friendly relationship continued until Johanna’s death (1842) and also lived on with her daughter Anna (known as Nancy), whom he called “Nimble.” A poem for little Anna dated March 20, 1813 has been preserved. Ernst Moritz Arndt also extended his lifelong friendship with Anna to her husband Louis Simon and his mother. In 1833, he became the godfather to Anna und Louis’s first son, Wilhelm. Wilhelm Simon died in 1916 at the age of 83. He was considered “one of the most distinguished personages from the era of the German private railways.” As a court assessor, he joined the Prussian state railway service. After several years in the Ministry of Trade, he worked for many years as chairman of the directorate for the Berlin-Hamburg Railroad Company until it was nationalized in 1884, at which time he was entrusted with managing the company. At the end of the 1880s, he was elected to the Prussian Parliament and joined the national-liberal caucus.

Johann Christian Dieffenbach (born February 1, 1792 in Königsberg, died November 11, 1847 in Berlin) was Johanna’s second husband. He studied medicine at the Albertina from the fall of 1814 until early 1820, and was a frequent guest in the Motherby household. He fell passionately in love with Johanna, who was nine years older and who returned his affections. Official investigations concerning “demagogic machinations”” (the founding of a fraternity) and his love for the wife of a respected Königsberg physician forced the 28-year-old Dieffenbach to leave Königsberg. Thanks to Johanna’s connections with Wilhelm v. Humboldt, Dieffenbach was able to take the state examination in Berlin in 1823 and to establish himself there as a physician. His practice thrived. He treated patients from throughout the world – both celebrities and the poor– and was the founder of plastic surgery at the Charité University Hospital.

Johanna and William were divorced in 1824. Johanna and Johann Christian Dieffenbach married in the same year. Dieffenbach wrote to a friend at the time: “My wife is not young, not pretty, and not rich; but precisely because she does not have all these things, you will be all the more convinced that I love her. On the other hand, she possesses an infinite wealth of goodness of heart and a delightful gentility, things that can never be lost.”

The marriage lasted only seven years, however. Dieffenbach divorced Johanna in 1831 and was remarried in the same year, this time to a woman 27 years younger than Johanna.

After her divorce from Dieffenbach, Johanna founded a salon in Berlin with her friend, Elisa von Ahlefeldt (divorced wife of Free Corps commander Major von Lützow), at which many well-known personalities socialized. She died on August 22, 1842 after a brief illness.

William Motherby survived Johanna by a few years, although he was plagued by ill health all his life. He “frequently defied death” (according to Prof. Ernst August Hagen in his memorial speech). In contrast to Kant, William Motherby drank “a glass of wine only for his friends’ sake.” William died in Königsberg on January 16, 1847, aged 70 and with his mental faculties intact. Motherby Street in Königsberg, now known as Lieutenant Roditeleva Street, was named after him in 1911.

Like his father Robert, William Motherby was a great lover of nature. In his memorial speech, Prof. Ernst August Hagen wrote that: “With a great deal of taste, he designed the garden of his residence, which now belongs to the Three Crown Lodge, and domesticated the swans in the Schlossteich (Lower Pond).” After 1832, William left Königsberg during the summer months (he continued to winter in Königsberg) and managed his Arnsberg estate with great success. He became director of the Society for the Promotion of Agriculture in Prussia and wrote a number of agricultural essays. He completely gave up his medical practice in 1840. In his last years, he authored an anthropological/psychological paper – which he dedicated to Kant – entitled “About the Temperaments,” which was published in 1843 by the publishing house Otto Wigand Verlag (Leipzig).

William’s younger brothers Robert (April 27, 1781 – August 1, 1832) and John (September 16, 1784 – October 19, 1813) also belonged to the Friends of Kant Society founded by William Motherby. Robert and William were particularly close. Robert was initially a merchant, not from inclination, but rather at his father’s wish. In contrast to his father, he was not successful in business. But he was a highly educated man, and later earned great recognition as a language teacher and linguist. In his memorial speech for William Motherby, Prof. Ernst August Hagen mentioned that his brother Robert was distinguished by his “persistence, perseverance, curiosity, diligence, sensitivity, honesty, humanity, kindness, modesty, and humor.” Robert published a dictionary of the Scottish dialect, followed by “English Language Exercises,” “The True History of Romeo and Juliet, Translated from the Italian of della Scala,” “Concerning Learning and Teaching of Modern Languages with Interspersed Comments on Speech and Language in General,” and many other works that earned him high accolades. The Royal German Society elected him as an ordinary member in 1830. He became seriously ill in the summer of 1832 and died on August 1, 1832 on a convalescent trip in Memel.

In his obituary of Robert Motherby in the Prussian Provincial Newspapers, the Evangelical theologian and poet Caesar von Lengerke described the manner in which Robert was influenced by his upbringing:

“His initial domestic education under the eyes of his knowledgeable and sensitive father must have been well suited for quickly awakening the young boy’s spirit to brisk activity and promoting the development of his mind. The pleasant external circumstances of the wealthy and respected merchant, whose house was a model of fine manners and witty society, and which enjoyed the society of outstanding men of the time such as Kant and Hippel, also favored the first efforts for such an education. Our Robert is yet again proof that the earliest impressions we experience in our father’s home should be considered as the most enduring for the entire life. Paternal esteem was immersed in the purest, most tender form of love, and thus the warmth and kindness of the child’s heart was also preserved. In a thoroughly decent and noble environment, in which the child’s tender feelings were universally spared, a sense of decency and humanity was easily awakened and became a lasting part of his character.”

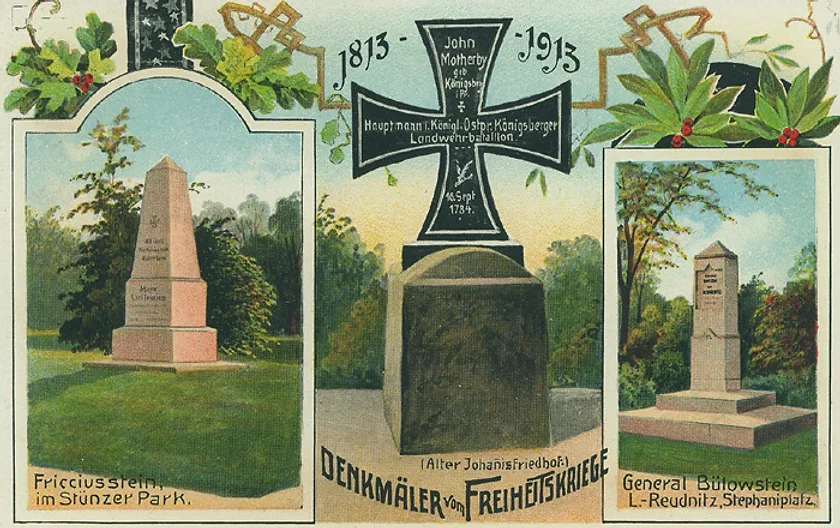

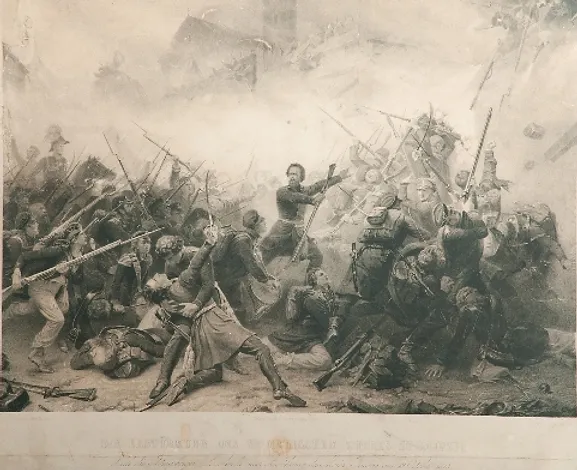

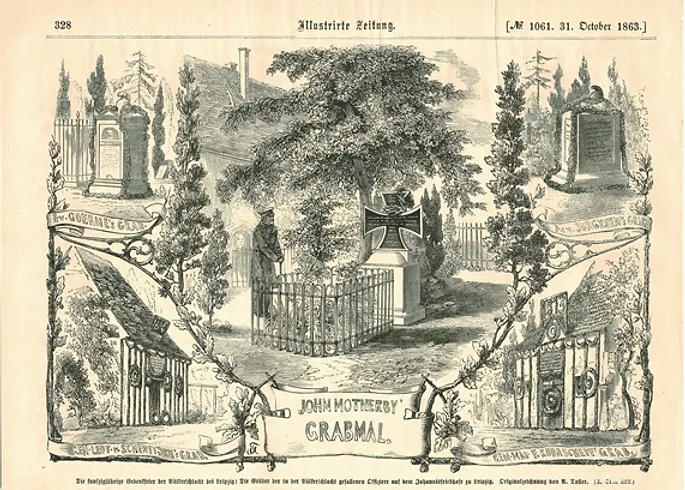

Like his brother, William’s youngest brother John (born September 16, 1784) was a multifaceted man. Following his study of law, he wandered through Germany and Europe for two years, visiting both Paris and Genoa, and following his return became a member of the Governing Council in Königsberg. When Prussia declared war on France on May 17, 1813, John Motherby volunteered for the Königsberg Territorial Army and fought against Napoleon on the side of the Russians. He fell in the Battle of Leipzig on October 19, 1813, during the storming of the Grimma Gate. There is a tombstone in his memory in the Alter Johannisfriedhof behind the Grassi Museum in Leipzig.

Source: https://geheimtipp-leipzig.de/postkarten-vom-denkmal-ii/

His friend, the poet Max v. Schenkendorf (1783-1817) of Tilsit, immortalized him in the following poem:

“On the death of John Motherby, Royal Governing Council Member and Captain of the Königsberg Territorial Army 1813.

Alas! A man has lately fallen,

One among the faithful host,

Which with bright sparks of heaven glowing,

This year arose to take its post.

Like a hero on his shield

He lies at Leipzig’s gate

Upon the pleasant German fields

The Lord chose for his final fate.

Are we to lose you now so soon?

O Captain, your dear company

Desires no other, only you,

And will preserve your memory.

Father’s house and father’s ways

And freedom were the things you loved,

Your English father taught you well,

His values flowed within your blood.

And as the strength within you grew

freedom’s dawn shone bright and clear,

In Saxony, the lovely land

Your death for freedom waited near.

The news of your heroic deed

Will reach the city of your birth,

Whence God and justice hand in hand

Sent forth our host to prove its worth.

Laid here to rest in German soil

Near unto Gellert now interred;

That we be worthy of your death,

Our prayer unto the Lord be heard.”

© 2015 Marianne Motherby

Translation: Terence Coe